In late October I walked through Woodford County High School during a farewell tour. The building was destined to become “the old high school” at the end of 2024, and “the new high school” would open in January.

I am fond of that old building. My dad was on the school board when the Midway and Versailles, Kentucky, high schools were consolidated; the building opened in 1964. I’m a graduate; my wife, Mary Beth, taught there for eighteen years; and our sons, Steele and Clay, are graduates, too. As a student in the building, I experienced success and humiliation, love and rejection, laughter and … more laughter. Whenever I was there as an adult—as a father and a husband—I experienced pride, always pride.

As you might guess, Woodford County High School didn’t look exactly the same in 2024 as when I graduated in 1976. The space that had been the library—my homeroom for four years—was transformed into classrooms decades ago. Renovations had similarly rendered other old haunts—Mrs. Vaughn’s classroom and the band room—recognizable, but not the same.

What did look the same were two large spaces: the cafeteria and the gym. Both of them play prominently in my memories.

I ate a school lunch in the cafeteria every single day; I never brought my lunch, and I never skipped school. That same cafeteria was also the site of every school dance: Homecoming, Christmas, Sadie Hawkins, and the prom. And with a stage at the non-cooking end, the cafeteria also served as the school theater. My acting career started and ended during my senior year, when I bluffed my way through roles in two productions on that stage.

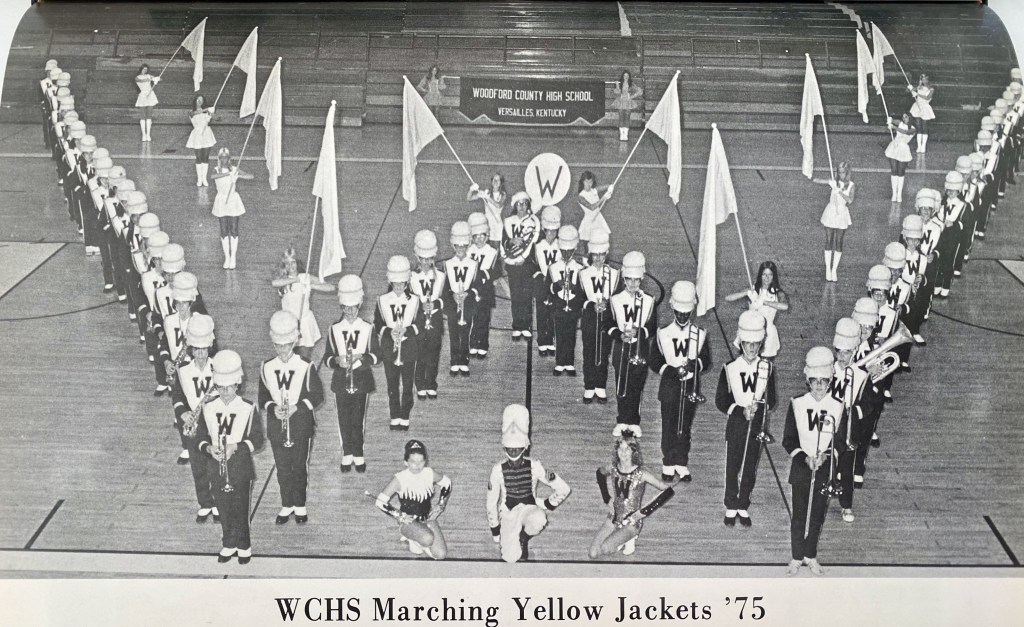

After 1976, I never ate lunch, danced (badly), or acted (even worse) again in the cafeteria, but the gym was different, as it was prominent in my life for another forty years. During my school days, I was no athlete, but I attended many a wrestling match and a ton of basketball games. (I was a real playuh, but in the pep band.) Also, I didn’t win any awards to speak of, but I was in the gym for several honors nights through the years, and I was in the bleachers when the community celebrated the 2012 state champion baseball team, which Steele was on.

I was also in the gym for a few graduation ceremonies, including my two sisters’ and my own. I remember nothing from Amy’s ceremony in 1974 and little from my own diploma grab in 1976, but I certainly recall June 5, 1972, when I was there to watch my oldest sister, Kay, graduate.

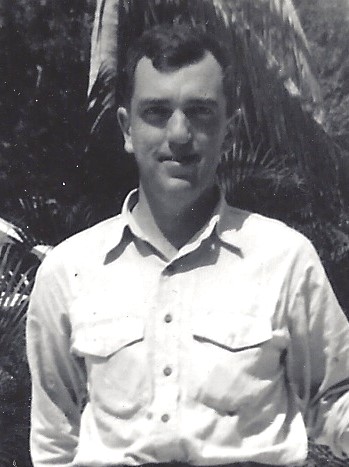

At fourteen, I was embarrassed of my family. That’s hard to understand now. My very normal parents were solid citizens and contributed to the community. Heck, Dad’s name was on a plaque at the entryway of the high school. Both of my sisters were well-liked and successful: Amy was a varsity athlete and Kay was the co-valedictorian of her graduating class. But I was an insecure teenager, and even though my family was not cringe-worthy, I cringed nonetheless.

I’m sure Mom, Dad, Amy, and I sat together during Kay’s graduation ceremony, but I only remember being beside Dad. See, I was hyperaware of my father’s clapping. He had a way of cupping his hands that made his slow, methodical claps rather loud. That was fine in a crowd, but the thing was, he clapped too long.

During the ’72 ceremony, whenever there was a round of applause for a pronouncement or introduction—and there were many—my father continued to clap after everyone else had stopped. Over and over, he performed a solo of sorts: a solitary clap (or two, even!) after the general applause had fallen silent. Although I didn’t actually see anybody scan the audience to look for the long clapper, I was sure everyone was asking the same question.

“Who is that person clapping an extra clap?” they had to be wondering. That person was my father, and I would be forever known as the son of the long clapper.

Each graduating senior’s name was called as they strode across a temporary stage, followed by applause … which was in turn followed by my father’s lone-wolf clap. And after the diplomas came the speeches.

Honestly, I can’t tell you anything about the speeches. I feel certain there were inspiring words from the principal or the superintendent—maybe both—and the guest speaker was a titan of local industry. I am also certain that the other co-valedictorian and the salutatorian delivered a speech. I don’t remember a single word from those addresses, though.

What I do remember is that my sister … sang.

As the class co-valedictorian, Kay tied for the highest GPA in a class of two hundredish, which is a heck of an accomplishment. It earned Kay a spot on the podium with the opportunity to address her classmates, her teachers, and the entire gathering. She could have talked about collective aspirations, shared values, or hopes for the future. She could have regaled the audience with school day memories of good old Woodford High. Instead, she sang a song.

It was a perfect song; I’ll give her that. “Friends with You” was released as a single in the fall of Kay’s senior year. John Denver—in his oh-so clear voice—sang the verses in haunting minor chords before swinging into a major key for the chorus:

Friends, I will remember you,

Think of you, pray for you.

And when another day is through,

I’ll still be friends with you.

Kay, too, sang with a nice, steady voice, and she had learned to play the guitar as an accompaniment. Expressing herself through a song rather than a speech must have come as a welcome relief to her classmates, her teachers, and every person in the audience.

Except her brother. I had already been red-faced for an hour or so because my father, you know, clapped his hands, and then my sister went and did something so … unconventional.

I ask you to think back to your own teenage days—to your embarrassing family—and try to imagine how I handled that situation. You’ll have to imagine it, and I will, too, because I can’t tell you how I handled it. I guess I went into a trance.

I don’t know what I was worried about, really. I bet none of my friends were there that day. And if there had been a classmate of mine in the crowd—dragged to the gym because they, too, had a graduating sibling—I feel safe in saying they did not connect the singing senior with the nerd in their eighth-grade science class (me). But still, I felt the weight of the world’s eyeballs. And they were rolling—hard. I would be starting high school myself in three months, and I was already nervous about fitting in. I’m sure my blanking out was a means of self-preservation.

I can’t tell you if Kay’s classmates were smiling, nodding, and tapping their feet. Perhaps they were even singing along. Maybe the whole crowd was singing along. Who knows? Not me.

What I can tell you is that fifty-two years later, during a farewell tour of the Woodford County High School building I’d known most of my life, I found myself standing at the end of the gym floor where they used to set up chairs, a lectern, and a microphone for graduation ceremonies. I was standing, purely by chance, in about the same spot where Kay stood in front of her entire world, strummed a guitar, and sang to her friends.

I know something now I didn’t know then: If you want your message to get through, you need to step out of the box. You have to differentiate your delivery to cut through the clutter and get your point across. I’m guessing that, prior to Kay Coleman Rouse, every valedictorian in Woodford County history had made a mushy speech that blended in with the rest of the graduation jabber. Kay could have given a speech. She could have told her classmates she loves them and she’ll always remember them. But instead, she sang those words … sending her message straight into the hearts of her friends.

Convention is safe and reliable. But it’s also predictable, and words delivered in conventional ways—in stale orations—can wash right past listeners. Kay delivered words with meaning in a style all her own.

What a gutsy chick.

As I stood there in 2024, I looked up to the spot in the bleachers where I sat with my family on a June evening in 1972. Because of the memory hole that opened shortly after Kay started singing, I can’t say how the rest of her performance went. My next memory of that evening is the applause from the crowd when Kay finished. Everyone was clapping. They seemed to appreciate Kay’s music—her courage—and they clapped for a long time. And then they stopped.

Well, most of them stopped. Into the silence, my dad shot a single, final clap.